𝐖𝐡𝐞𝐧 𝐅𝐥𝐨𝐨𝐝𝐬 𝐁𝐫𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐅𝐨𝐫𝐭𝐮𝐧𝐞: 𝐇𝐨𝐰 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐈𝐧𝐝𝐮𝐬 𝐃𝐞𝐥𝐭𝐚 𝐁𝐫𝐞𝐚𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐬 𝐀𝐟𝐭𝐞𝐫 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐌𝐨𝐧𝐬𝐨𝐨𝐧

Dawn at the Delta

We left Nagar Thatta before sunrise. After four days of relentless monsoon rain the entire world looked rinsed—Makli’s ancient ridge, the highway, the low houses—everything wore a damp sheen. Being so close to the coast, the air carried invisible droplets, laying a pale blue film over the landscape. We stopped in Thatta for breakfast and two cups of sweet tea, then turned the car toward Shah Bandar and Keti Bandar. Water shimmered in roadside ditches, but the keekar trees were in fresh leaf, as if celebrating.

Before describing today’s delta, it helps to listen to older witnesses. Nearly seven centuries ago, in 1333 CE, Ibn Battuta descended the Indus by boat and entered this maze of creeks. “The Indus is among the great rivers of the world,” he wrote. “Just as Egypt’s agriculture depends on the Nile’s flood, so do the people here live by this river’s inundation.” Two centuries later, in 1592, the Mughal commander Abdur Rahim Khan-i-Khanan echoed the sentiment when he marched on Thatta: southern Sindh, he noted, was laced with canals like old Baghdad, dotted with ghats and harbors, rich in rice, cane and indigo, and alive with fish and birds.

Back then, the Indus split north of Brahmanabad and fanned across the plains. One branch slipped east of Nasarpur and past present-day Tando Mohammad Khan; others skirted Thatta before meeting the sea near Debal and Lari Bandar. Ibn Battuta called Lari Bandar “a handsome city by the sea” where ships from Yemen and Persia traded, bringing wealth and heavy tax revenues to the sultan’s coffers.

Downstream of Kotri: Lives Tethered to Flow

When we say “Kotri downstream,” we mean the Indus Delta—thousands of villages and hundreds of thousands of people south of Kotri who live by the flow. When that flow is throttled, sand rather than sweet water pours down. Villages empty, households tie up their lives in bundles and move on.

The throttling began with empire. In the 1830s the East India Company laid an irrigation system to feed its mills. In 1932 the British raised the Sukkur Barrage, the first great attempt to tame the river’s beautiful madness. Post-Partition came Kotri Barrage (1955), Mangla Dam (1967) and Tarbela Dam (1976). Each project brought agricultural benefits upstream; each cast a long ecological shadow on the delta.

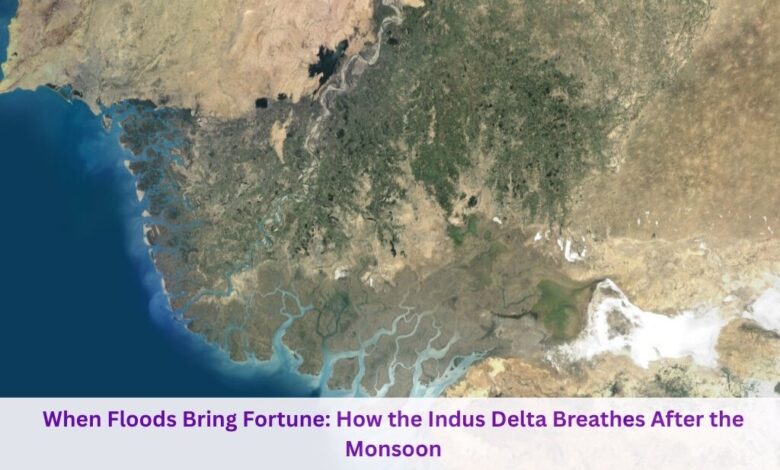

A river’s last miles have their own aesthetic. Southern Sindh’s coast is literally built from the Indus—its silt and sand. Lakes once speckled the terrain because this is where a 3,000-kilometer journey ends. Few rivers on Earth have shifted course as often as the Indus has while seeking the sea. From the Sirr Creek on the southeast (now a border marker) to Khobar, Kalanri, Ghoro, Dabbo, Phitti, Korangi and Gizri in the west, a web of creeks carries tidal water in and fresh water out. These are the river’s many doors to the ocean.

The River That Builds Land

Not all rivers are equal architects. Some carry little sediment; others haul continents. The Indus belongs to the latter class, rivaling and often surpassing the Nile in fertile silt. Watch the flood and you’ll see thick, tea-colored water—a broth of minerals and nutrients that feed marshes, plankton, fish, and finally people.

Where that silt falls and settles, deltas are born. Imagine the Indus nearing the sea: seeing the ocean’s resistance, the river spreads like a hand fan, drops its load, and quietly creates land. In windy seasons the sea strikes back, pushing the river into multiple branches, but the silt keeps coming, raising sandbars into shoals, shoals into islands, and islands into fields.

History records the pace. In 1877, colonial surveyors calculated that the Indus’s multiple mouths had produced three and a half square miles of new land in just ten years. In years of flood, estimates suggest the river could push nearly 120 million cubic yards of silt seaward in 100 days—roughly three times the Nile’s annual sediment.

No wonder the delta was once a byword for abundance. Rice needed hardly any coaxing: farmers broadcast seed and paddy rose like a forest. James McMurdo wrote of stalks three to four feet tall, and harvesters came from Kutch and Multan to cut the vast crop. James Burnes crossed the delta in the early 1800s and heard birdsong from reedbeds, watched sugarcane irrigated by waterwheels turned by camels and oxen, and saw fish so plentiful “it seemed they were born here.”

Contraction and Salt: A Century of Unmaking

Abundance can be unmade. As Alice Albinia notes in Empires of the Indus, the completion of Kotri Barrage in 1958 marked a turn. The once 3,500-km² active delta shrank to 250 km². Sweet water barely reached the sea. Mangrove forests withered; rice lands turned white with salt; thousands of farmers became reluctant fishermen because nothing else remained.

How much water does the delta need? That question has sparked arguments among governments, engineers, environmentalists and fishing communities for decades. A study by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) estimates the delta requires 27 million acre-feet (MAF) annually to sustain mangroves and hold back the sea. Fisherfolk organizations argue the true ecological need is closer to 35 MAF. The 1991 Water Accord promised 10 MAF below Kotri; in practice, even that minimum has often gone unmet.

The consequences have been brutal. Without freshwater pulses, the sea advances, salting fields and drinking water. Mangroves—nurseries for commercially important fish and shrimp—collapse. By the government’s own accounts, 1.2 million acres had been lost or salinized by 1980; today the figure is closer to 3.5 million acres. Lakes are degraded, wildlife thins, and families migrate inland. It is not just land that erodes; a culture erodes with it—the Mohana fishing culture shaped by tides, creeks, reeds, and rain.

The Monsoon Arrives: When Flood is Fortune

And yet, in years like this one, the delta smiles. Monsoon downpours swell the Indus; around 300,000 cusecs—roughly 6 MAF—are presently spilling through the delta’s arteries toward the sea. From the Doolah Darya Khan bridge near Thatta, the river forks: one branch runs through Rohra and Kharo Chhan toward Shah Bandar; the other heads for Keti Bandar, then the Khobar, Tirchan, and Hajamro creeks. Across 80+ kilometers, sweetwater pushes saltwater back.

For delta dwellers, these are days of Eid. Fields, forests and lakes drink deeply; dormant grass wakes; brackish channels turn sweet miles inland. “Sail toward Kharo Chhan,” a local activist in Jhalo told us, “and you’ll taste river water in the sea. We drink from it when we’re thirsty at anchor.” With sweetwater come nutrients—the fine particles fish feed on and shrimp larvae need to grow. If last year’s catch was meagre, this year the same nets could return triple.

Engineer Oobhayu Khushk in Thatta explains the mechanics. Freshwater brings silt rich in nutrients to the mangrove roots, speeding growth. Mangroves, in turn, are carbon sinks, absorbing large amounts of CO₂ while also sheltering fish nurseries. The freshwater pulse also recharges aquifers, raising the water table in nearby settlements. “Right now,” he says, “the delta’s people are very, very happy.”

Why Freshwater Matters to the Sea

It sounds paradoxical, but sea health near a great river depends on river health. Freshwater moderates surface temperature along the coast, supports a wider continental shelf, and feeds a food chain from plankton up to commercial fish. Sindh’s shelf stretches about 110 km into the sea—considerably broader than Balochistan’s 30–35 km—because the Indus has built it grain by grain. The broader the shelf, the richer the fishery. Take away the river’s silt, and you shrink both shelf and livelihood.

That is why the battle for environmental flows below Kotri is not romanticism. It is climate realism. Freshwater is a thermostat, a nutrient pipeline, a wall against salt intrusion, and a gardener for mangroves—all at once.

People, Place and the Making of Culture

Every region shapes a livelihood; every livelihood shapes a language, a rhythm, a dignity. Along the creeks a person may be born, grow up, bury grandparents, launch a marriage boat, and measure the year by tides rather than months. You cannot tell such a person to plant cane where the shore breathes or to sow wheat where nets must dry. Culture is not an interchangeable tool; it is a long treaty between people and their place. Good delta years nourish that treaty; bad years tear its pages.

The Road Ahead: Keep the River a River

What, then, should policy learn from seasons like this one?

- Guarantee a minimum environmental flow below Kotri—faithfully, not ceremonially. Whether the number is 10, 27 or 35 MAF can be argued in technical forums, but the principle cannot: a delta without river is a desert with tides.

- Treat mangroves as national infrastructure. They are storm buffers, carbon sinks, hatcheries and land binders. Restoration should be continuous, not campaign-based.

- Monitor the shelf and fisheries with modern science tied to community knowledge. Fisherfolk know when the sea turns “thin” or “hot”; combine that knowledge with satellites and sensors.

- Share the river’s costs and gains fairly. Upstream prosperity should not mean downstream ruin. Water accounting must include ecology and culture, not only acreage.

Back on the Road

As we drove back from Keti Bandar, the villages around Jhalo felt lighter. Nets were being stitched, boats refitted, children chased each other along the bunds. When the Indus is generous, the delta remembers how to live. Flood is not always a calamity; here, at the river’s end, it can be a permission slip for prosperity—a reminder that the sea does not begin where the land ends, but where the river keeps its promise.